Elliptic curve attacks - from small subgroup attack to invalid curve attack

TL;DR

When auditing elliptic curve libs, especially ECDH related code, double check if the code has sufficient validation on the points sent by the users. If not, attacker can send bogus points to trick the backend server, recovering server’s private key in the worst case.

There is a well-known attack called “small subgroup attack”, where the attacker can pick a point from a subgroup with small order and send to the server. Since order (number of elements in the group) is small, it is easy to bruteforce the shared secret and thus decrypt any encryption in the communication. This attack also reveals server’s private key modulo the order of the point you chose. To prevent this attack, the server should verify if the point is chosen from a known subgroup, or simply pick a curve with prime order (so that there is no nontrivial subgroup).

Another lesser-known attack is called “invalid curve attack”, the idea is built on top of small subgroup attack. In this attack, attacker picks points with small order from many “similar” curves (differs only in constant term) and sends them to the server. For each point, attacker learns a congruence of server’s private key. In the end, attacker collects a system of congruences and solve the private key using Chinese Remainder Theorem. To prevent such attack, the code should verify that the incoming point satisfies curve equation.

I am writing this article since I found most existing articles don’t explain the details (especially math details) very well. When reading those resources, I had been confused multiple times due to lack of explanation. Therefore I will try my best to make sense all the steps in these two related attacks.

Feel free to DM me on Twitter if you find mistakes in this article.

Prerequisite readings

You need to understand basic abstract algebra and how elliptic curve works, but shallow understanding is enough. I recommend the following articles:

- https://www.rareskills.io/post/set-theory

- https://www.rareskills.io/post/group-theory-and-coding

- https://www.rareskills.io/post/rings-and-fields

- https://www.rareskills.io/post/elliptic-curve-addition

- https://www.rareskills.io/post/elliptic-curves-finite-fields

- https://andrea.corbellini.name/2015/05/17/elliptic-curve-cryptography-a-gentle-introduction/

- https://andrea.corbellini.name/2015/05/23/elliptic-curve-cryptography-finite-fields-and-discrete-logarithms/

Some (sub)group theory: Lagrange’s theorem and Cauchy’s theorem

We will need some group theory results to understand why small subgroup attack and invalid curve attack work. This part is missing from most of the articles / ctf writeups on the Internet, so pay attention. We are going to cover two theorems regarding subgroups: Lagrange’s theorem and Cauchy’s theorem.

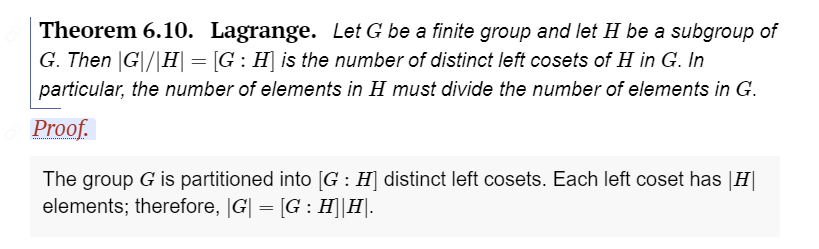

Lagrange’s theorem:

Reference: http://abstract.ups.edu/aata/cosets-section-lagranges-theorem.html

Here is short intro to cosets and Lagrange’s theorem on Youtube. Basically this theorem says if \(H\) is a subgroup of \(G\) then the order of \(H\) divides the order of \(G\). For example, say \(G\) is a group of order 12, then the only possible subgroups are subgroups of order 2, 3, 4, and 6, not counting the trivial subgroups \(\{e\}\) and \(G\) itself. Note that it does not mean there are only four non-trivial subgroups: multiple subgroups with the same order can exist.

The idea for proving Lagrange’s theorem is that cosets partition a group \(\)G\(\) and all cosets have the same size. Moreover, each coset \(gH\) has the same size as the subgroup \(H\). Visually, you can think of the group \(G\) is a chocolate bar and each coset is a chuck of it. You can prove that all cosets are pairwise disjoint, which means they don’t overlap. It is easy to see that the order of the group is just the sum of the order of all cosets, so the order of each coset divides the order of the group, therefore the order of each subgroup divides the order of the group (since order of \(gH\) is the same as the order of \(H\)). Not a formal proof, but you get the idea.

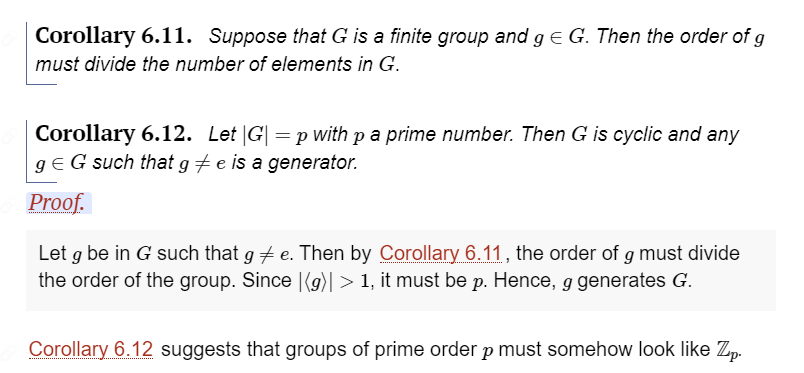

Lagrange’s theorem has two important corollaries:

Reference: http://abstract.ups.edu/aata/cosets-section-lagranges-theorem.html

The first corollary is very easy to understand. The second corollary is saying “any group with prime order \(p\) is a cyclic group and any element other than identity is a generator”. Recall that elliptic curve over finite field is a group, therefore these two corollaries apply to it. In elliptic curves, the first corollary says the order of a point on elliptic curve always divides the order of the curve. The second corollary says for any curve with prime order, the curve is cyclic and all points besides point at infinity are generators.

These two corollaries are important results, keep that in mind, we will use them a lot when studying elliptic curves.

And ATTENTION, you should know that Lagrange’s theorem is an if-then theorem: if \(H\) is a subgroup of \(G\), then the order of \(H\) divides the order of \(G\). It does not guarantee the existence of a subgroup of a certain order. Equivalently, this reasoning is saying “the reverse of Lagrange’s theorem is false”: if the order of \(H\) divides the order of \(G\), \(H\) might not be a subgroup of \(G\). Fortunately, the reverse of Lagrange’s theorem is sometimes true, when \(H\) has prime order.

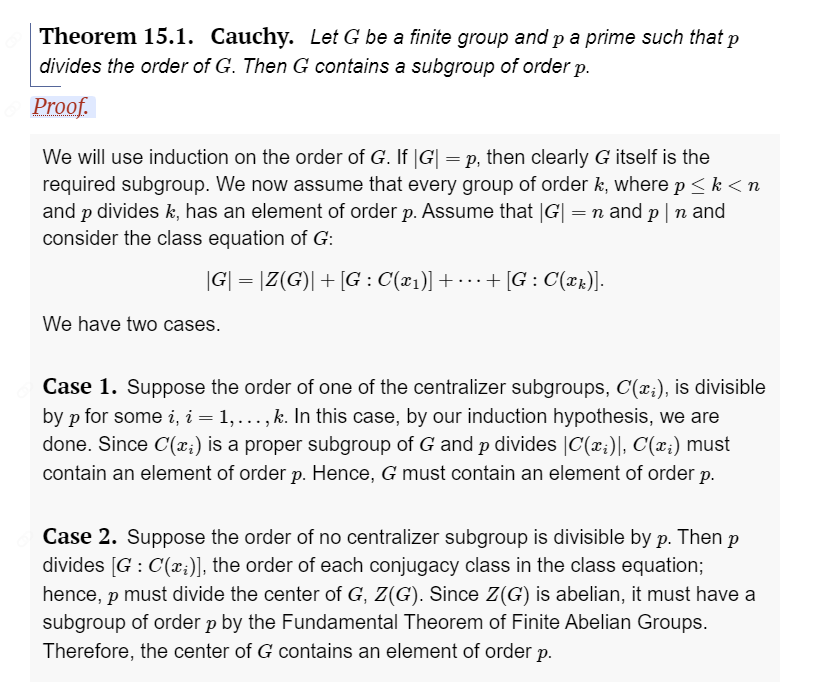

Cauchy’s theorem:

Reference: http://abstract.ups.edu/aata/sylow-section-sylow-theorems.html

For example, say group \(G\) has order 6. We can factor 6 into prime decomposition: 6 = 2 * 3. Cauchy’s theorem guarantees that subgroups with order 2 and 3 exist. In summary, Lagrange’s theorem tells you what are the possible subgroup orders, and Cauchy’s theorem tells you subgroups of prime orders (prime factors of \(G\)) actually exists.

Recall the second corollary of Lagrange’s theorem says any group of prime order is cyclic, and any element other than identity is a generator. Combining it with Cauchy’s theorem, the prime order subgroups we get are all cyclic, and any (non-trivial) element in the subgroup is a generator. Recall that first corollary of Lagrange’s theorem says the order of an element in a group divides the order of the group. Since we are working with prime order subgroups, it is easy to see that the order of element is either 1 or \(p\), where \(p\) is the order of the prime order subgroup. The order 1 case corresponds to the identity element, so we can conclude that if prime order subgroup has order \(p\), then any non-trivial element in it has order \(p\) as well.

You might ask, why bother studying subgroups though? Abstractly, think of taking subgroup as reducing a big problem to a small one. In the two attacks we are going to talk about next, you will see how taking subgroups converts a hard problem into easy problem (computationally).

Understanding Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH)

ECDH is like traditional Diffie-Hellman (DH), but replaces the original discrete log problem (DLP) with elliptic curve discrete log problem (ECDLP). In short, DLP means given \(y = g^x \mod p\), it is hard (hard means nearly impossible) to recover \(x\). In comparison, ECDLP means given \(Q = nP\) where \(P\) is some point on an elliptic curve over a finite field, it is hard to recover \(n\).

In general it is recommended to use ECDH over DH since it has shorter key, up-to-date standard and less attack vectors. However, if you don’t implement ECDH correctly, it is still vulnerable to attacks such as small group attack and invalid curve attack.

The motivation of DH is to exchange a shared key over insecure channel and use that shared key for future symmetric cryptography communication. The same idea applies to ECDH. This type of system is called “hybrid encryption”, inheriting the security of public-key cryptography and the speed of symmetric cryptography.

In ECDH, Alice and Bob agree on a point \(G\) on some elliptic curve, each of them compute public key based on private key. This step is just elliptic curve multiplication: Alice computes public key \(Q_A = d_A * G\) and Bob computes public key \(Q_B = d_B * G\), where \(d_A\) is Alice’s private key and \(d_B\) is Bob’s private key.

The next step is key exchange. They can just publish \(Q_A\) and \(Q_B\) on the Internet (insecure channel), since attacker can’t crack for \(d_A\) and \(d_B\). The hardness is guaranteed by ECDLP.

In the end they compute a shared secret (this is the shared key) using their private keys again, the formula is \(key = d_A * d_B * G\). That is equivalent to say, Alice multiplies Bob’s public key by her private key, and Bob multiplies Alice’s public key by his private key. After that, Bob can send encrypted messages to Alice using this shared key.

Small subgroup attack

Small subgroup attack is a building block of invalid curve attack, so we discuss it first.

First, for small subgroup attack to work, the curve must have composite order. This is easy to understand since we just talked about Cauchy’s theorem: if the elliptic curve has prime order, then the only subgroup with prime order is itself. There is no concept of “small subgroup” for curve with primne order \(p\) since the factors of a prime \(p\) is just 1 and \(p\). In other words, curves with prime order don’t have small subgroups thus immune from small subgroup attack.

Consider a ECDH protocol where Bob does not validate incoming points from Alice sufficiently. Usually a standardized curve will have order of the form \(n = q \cdot h\), where \(n\) is the order of the curve, \(q\) is a large prime which is also the order of a predefined point \(P\) on curve, and \(h\) is some small integer called the cofactor. In reality this cofactor is 1, 4, or 8, so fairly small.

When Alice conducts small subgroup attack, she can pick a point \(Q\) with order \(h\) instead of \(q\). You might ask, how do you know point of order \(h\) exist? (This is called h-torsion point, where torsion point means point with finite order on an elliptic curve. h-torsion means the order is \(h\), that is, \(hP = O\) where \(O\) is point at infinity.) Recall that elliptic curve itself is a group structure, therefore Lagrange’s theorem works for elliptic curve points. By Lagrange’s theorem corollary 1, the order of an elliptic curve point divides order of the curve. Since order of curve is \(n = qh\), if order of point divides \(n\) then it must divide \(h\) as well. We have discussed that if \(h = 1\) then the curve is immune to small subgroup attack. Excluding that, we would consider:

- \(h = 4 = 2^2\) -> point can have order 1, 2, or 4

- \(h = 8 = 2^3\) -> point can have order 1, 2, 4, or 8

Without getting stuck into details, let’s say Alice can find a point \(Q\) with order \(h\). She sends \(Q\) to Bob, Bob computes \(d_B * Q\) and use that as shared key to encrypt further communication. Since \(Q\) has small order \(h\), there are only \(h\) possibilities for \(d_B * Q\). Why? We know that a subgroup of a cyclic group is cyclic. Since \(Q\) is from a subgroup of the curve and standardized curves are cyclic in general, Alice is actually finding the answer inside a cyclic group of order \(h\). What she can do is keeping adding the point to itself and see which candidate is able to correctly decrypt the encrypted message. This will take 4 or 8 tries depending on the value of \(h\).

(TODO: I still don’t know how to prove a point with a certain order actually exist on a curve and I don’t have an algorithm for finding it. Will come back later if I figure out).

To prevent small subgroup attack, your code should reject any incoming point \(Q\) s.t. \(hQ = O\) from Alice. Another way to prevent this attack is to set \(h = 1\), so that the order of curve will be a large prime.

Invalid curve attack

If Bob does not verify if \(Q_A\) is actually on the elliptic curve (call it valid curve), Alice can come up with some fake point which lies on some other elliptic curve (call it invalid curve). For example, if the valid curve is BN254 -> \(y^2 = x^3 + 3\), then Alice can choose invalid curves \(y^2 = x^3 + c\), where \(c\) is a constant. You might ask, why keep \(x^3\) fixed and only change the constant term? It is because elliptic curve addition law does not involve the constant term, so that Bob can compute without panic even though the point sent by Alice is on a different curve. This fact can be verified with simple algebra. Check this answer for full derivation.

Invalid curve attack is superior compared with small subgroup attack since we have more degrees of freedom. We can pick a point with order \(p_1\) from a curve, pick point with order \(p_2\) from another curve, then point with order \(p_3\) from another curve, and continue. Recall that in small subgroup attack we could just pick point from a subgroup of the same curve, so choices were a lot more limited.

Back to the actual attack. Alice then chooses a point \(Q_1\) on the invalid curve with small prime order \(p_1\). Alice sends \(Q_1\) to Bob in the key exchange phase. Bob would compute key = \(d_B * Q_1\), where \(d_B\) is Bob’s private key. In the end Bob will encrypt message using this computed key and send ciphertext to Alice.

Once Alice receives ciphertext, she can bruteforce the shared key. Since \(p_1\) is fairly small, the shared key \(d_B * Q_1\) only has \(p\) possible values. Alice can traverse all possible points on the invalid curve and see which point decrypts the encrypted message correctly (for example it should return some meaningful string). In this round, Alice learns a congruence relation \(d_B \mod p_1\). It is not possible to learn \(d_B\) in only one round since we are working with elliptic curve on finite field, so anything we compute is in mod \(p\).

To recover \(d_B\), Alice chooses point \(Q_2\) with order \(p_2\), point \(Q_3\) with order \(p_3\), and so on, and repeat the above process. In the end, Alice gets a system of congruences. Since all modulus \(p_i\) are prime, they are coprime to each other. This satisfy the criterion of Chinese Remainder Theorem (CRT), so Alice can solve for \(d_B \mod p_1*p_2*...*p_n\). If Alice gets enough congruences so that the modulus \(p_1*p_2*...*p_n\) is large enough, \(d_B\) will be in the simplest form so no need to worry about modulus. In other words, Alice is able to recover Bob’s private key at this stage.

To prevent this attack, Bob should verify all points sent by Alice satisfy the Weierstrass equation of the valid curve.

Other references not mentioned in article

- https://safecurves.cr.yp.to/twist.html

- https://crypto.stackexchange.com/questions/18222/difference-between-ecdh-with-cofactor-key-and-ecdh-without-cofactor-key/26844#26844

- https://www.hackthebox.com/blog/business-ctf-2022-400-curves-write-up

- https://crypto.stackexchange.com/questions/43614/how-to-find-the-generator-of-an-elliptic-curve